-

Sarah Cowper’s Family Books: Research Interns’ Report

By Abigail Wilkinson, Charlotte Bell, Dion Reid, and Victoria Barnard

[This summer, the Family Archives project was joined by four 1st and 2nd year undergraduate students as part of the University of Birmingham’s Research Internship scheme. Together, they have been working on the family books compiled by eighteenth-century gentlewoman Lady Sarah Cowper. They gave a paper on their research at the recent ‘Family Archives & their Afterlives’ Conference (27 & 28 June 2023): the report below summarises their initial findings and experiences…].

Sarah Cowper (1707-1758) was the daughter of William, 1st Earl Cowper and Mary Clavering, Countess Cowper, as well as the granddaughter of famed diarist Dame Sarah Cowper. In comparison with her more famous forebears we know relatively little known about ‘our’ Sarah’s life. She died unmarried and childless, and her ‘family books’ appear to be the most significant thing left behind after her death. Comprising of 8 volumes and spanning the years 1692 to 1737, these books are a compilation of the letters, diaries, and assorted other writings penned or preserved by her ancestors, partially and selectively transcribed and arranged in chronological order. Sarah inherited these family papers after the death of both her parents in the winter of 1723/4, but we aren’t entirely sure when Sarah produced the books. Based on the way some people are referred to, and which dates are included, we believe she started her project sometime in the 1740s.

[Pages from Volume 6 of the Family Books. Reproduced by kind permission of Hertfordshire Record Office].

Volumes 1 and 2 are made up of correspondence between Sarah’s mother, Queen Anne and the Duchess of Marlborough. The first part of book 2 covers the intertwining political and social tensions amongst members of Queen Anne’s Court from 1706 up until her death in 1714. The second half of book 2 is based on Dr David Hamilton’s memoirs, who was Physician to the Queen: through these entries Sarah frames the final years of the Queen’s life. The events in Volumes 1 and 2 took place during Sarah’s youth and represent an effort to frame her father and mother in a favourable light, both politically and personally.

The third book in the collection spans the tumultuous years 1714 to 1716 which are played out in the letters, diary entries and political speeches filling the volume’s pages. While working through the book, Lady Mary Cowper’s (Sarah’s mother) influence over the circles within the court and the political landscape was striking. Alongside her close relationships with figures such as the Duchess of Marlborough and the Princess of Wales, Mary’s fluency in French placed her in a position of power as she translated messages and treatises from her husband to the King. The focus on Mary’s papers makes this volume very similar to the first two Cowper books, suggesting that much of the family papers were preserved by Mary herself. The process of organising, transcribing and formatting her family papers was one that Sarah perhaps felt a duty to undertake after inheriting years of national and family history, yet while working through the volume we came to understand the sheer investment involved in Sarah’s project, and the time it would have taken to preserve these periods in her family history.

Book five spans from 1718 to 1720 and mostly consists of letters written to Lord and Lady Cowper by various members of the aristocracy, as well as drafts of their letters. Many of the letters in the book’s first part highlight the nobility’s response to Lord Cowper’s resignation of the Royal Seal and his position of Lord High Chancellor. Also, a significant number of letters comment on the estrangement between the Prince of Wales and King George I, and how Lord and Lady Cowper tried to reconcile them due to the quarrel negatively affecting English politics in a time of crisis. As well as including letters of political significance, Sarah Cowper includes letters about significant family events, such as when her family was ill with scarlet fever. Sarah also increasingly includes personal comments on the events which are taking place within the letters, such as describing how her parents took turns watching over her at night when she was ill as they were fearful she may die. Furthermore, Sarah includes information on historical events which were occurring during 1718 to 1720 in between the transcribed documents, such as the eruption of La Soufrière in 1718. This suggests that she expected the book to be read by future generations who would not have knowledge of these events, and to also provide the documents included within the book context, making the events and issues recounted more understandable.

Book six spans the years 1721-1729. It consists mostly of letters from William to Mary prior to their deaths, along with some political acts and events. Throughout this volume Sarah’s own comments increase as she would have been old enough to remember what she was doing at the time, such as attending balls and writing articles with her cousins. Furthermore, when she writes about her parent’s period of illness and their deaths, entire pages are taken up by her personal account of the events, paired with letters from family members and other powerful families. Partially because of this the books generally increase in length, with book one being approximately 170 pages, while book six is 370, this may also be because she became more passionate about the project or had a clearer idea of how to best tell the narrative. It was interesting to read Sarah’s comments as they increased through the book as it felt like it gave a sense of who she was based on what verses she picked, and which stories she chose to tell. This was especially noticeable since the books (although by her) are barely about her, therefore it was enjoyable seeing the small pieces of her own life preserved in the letters of others, and makes you wonder why she chose each thing she did. It also felt like you could see her opinion on a person based on what she chose to include about them.

[Panshanger House as depicted in Francis Orpen Morris, The County Seats of the Noblemen and Gentlemen of Great Britain and Ireland, vol 1 (1866).

It seems likely that Sarah Cowper’s Family books would have been stored in her family’s country home at Panshanger, Hertfordshire, and the books are now in the Hertfordshire Archives. We considered whether the volumes themselves were meant to have a social life as an archive. On this note, the Marlboroughs, who were close family friends and politically aligned to the Cowpers, exemplify this possible public intent. Sarah includes personal letters and ‘proof’ of accounts in defence of the Duchess of Marlborough after 1711- when she fell out of favour in court. In this way, these empirical accounts could be seen as a form of Sarah practising public family history. We are also working with the assumption that much of her reasoning for compiling these books was to paint her family (in particular her father) in a positive light, after several political scandals discredited the family name. This is apparent through Sarah’s inclusion of many letters praising her father’s political skill and loyalty, whilst leaving out some of the more scandalous aspects of his life. Furthermore, we found it interesting that a large portion of the letters are ‘extracts from’ rather than the letters in full which shows she is consciously creating a narrative, but we are not sure what sections have been missed out. Many of the transcribed documents still exist and an aim for the future is to compare the content to get a better idea of what Sarah viewed as unimportant.

Overall it was fascinating to work with these manuscript materials, as we had very little knowledge of the time period beforehand, and now feel like we have concluded our research project with a fascinating knowledge base through the lens of a woman in the 1700s. It was especially interesting to acquire this knowledge literally from her own hand, as we read pages of family history while deciphering eighteenth-century handwriting. It felt especially surreal knowing we were highlighting the voice of a woman who slipped through the cracks of history.

[Thanks to Victoria, Dion, Abigail, and Charlotte we now have a complete inventory of the items transcribed in the family books. I’m currently working on an article on these volumes, so watch this space].

[Delegates at the ‘Family Archives & their Afterlives’ Conference, where the Research Intern team delivered a paper].

-

Family Archives & their Afterlives Conference: a pupil’s perspective

By Lulu Frisson (student on a work experience placement in History at University of Birmingham)

I had the amazing opportunity to do some work experience and attend the ‘Family Archives and their Afterlives, 1400-present’ History conference at Birmingham University last week, helping out at the registration desk with UoB students and listening to a broad range of panels. It was a wonderfully new and exciting experience as, having just completed my GCSEs, most of my History education so far has been entirely from textbooks and worksheets. The knowledge I gained from all of the speakers and the archive material they discussed was invaluable and, in the days since, I’ve reflected on the rich and diverse range of talks I was able to attend.

My own family history

Perhaps the biggest thing I took away from the conference was a deeper interest and appreciation of my own family history and its preservation. Listening to panels as someone with absolutely no academic knowledge of archives meant I reflected far more personally on the content of the talks. Laura Beard’s presentation on her own family’s Scottish samplers was poignant and affecting, as was Dr Laura King’s reflection of her family’s ‘stuff, histories and stories’ and the wonderful ‘Reckoning with Romanticisation’ panel which looked at a diverse range of personal family histories. Dr King acknowledged the difficulties around objectivity and the emotional impact of using her own family’s archive in her academic research, but in all panels I attended I realised the fruitful ways each speaker’s own history impacted their work and I was moved, too, by the passion each had for their family’s stories. As I concluded my work experience week, I was struck by how interested I had become in my own family’s history. I now have a new appreciation for my grandfather’s painstakingly neat photo albums, my aunt’s insistence to keep anything and everything and my grandmother’s late night oral history lessons – all of which have allowed me to learn not only about world history and my family’s place in it, but also have strengthened my sense of identity and family relationships. It was not until attending this conference, though, that I realised how important it is for all of us not just to listen to our family’s stories, but also to research, retell and celebrate them.

[Dr Tamar Rozett, from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, opens the panel on ‘Diaspora’]

Technology and archives

Something I found striking and particularly relevant to my generation was a discussion in the ‘Objects and Emotions’ panel about the changing nature of archives and the role of technology in preserving – or, perhaps, destroying – the idea of a family archive. One question posed to the panel asked their views on the digitalisation of archive material, and their unanimous response – that close material work with physical sources is an irreplaceably important aspect of their research – made me reflect on the evolving role of technology and social media on family archives. Increasingly, for example, my parents will not frame our family portraits but instead keep them digitally, sharing them freely on social media. Increasingly, too, my cousins abroad will simply text or call me to stay in contact; the idea of sending a letter or card to a family member seems to be almost foreign to my generation. What this means for the future of the family archive and its study became a fascinating concluding discussion to two hours of equally fascinating talks which touched on the emotional impact of keeping and studying family archives. ‘How can we continue to preserve ‘us’?’ I jotted down as the panel came to an end.

Using archives in secondary schools, entertainment and beyond

Antonia Parker Smith and Caroline Pardoe’s talk on their musical theatre show, ‘Spinster of this Parish’, which covers West Midlands local history through the lens of one family, was both entertaining and inspiring. Having keenly studied Lin Manuel Miranda’s ‘Hamilton’ show at school, it was fascinating to hear of the complexities behind adapting history for entertainment and the ways in which bringing history ‘to life’ on stage can be rewarding for writers and audiences alike. Furthermore, Antonia’s mention of how the young actors of ‘Spinster of the Parish’ developed an interest in their own histories through their performance brought interesting questions to mind about the use of both family and national archives in education. Reflecting on my History education so far after the conference, I realised that most students won’t have an understanding of what an archive is, let alone work with actual letters and photographs within one – save for those printed in an exam textbook – until University. In Kristy Li Puma’s talk on the history of queer and trans familia in Washington DC she mentioned how she used material from the city’s archives in high school clubs and societies to develop students’ sense of belonging, and it occurred to me that analysing and discussing archive material in such clubs – particularly material from family archives, which provide a rich and personal look into all periods of history – would be invaluable in enhancing our understanding of both past and present. Already I am thinking of ways to incorporate material from Birmingham’s own archives into a school club for themed months like Pride Month next year, and I’m very excited to pass on my new interest and appreciation of family archives to my friends who love History too.

Attending the ‘Family Archives and their Afterlives, 1400-present’ conference was an invaluable experience and one which was educational in so many ways. The speakers inspired me in my own History studies as I move into Sixth Form but, more than that, their talks gave me a deep appreciation for my own family’s archive and a space for reflection on my personal history. I’m very grateful to Dr Imogen Peck for organising the conference and letting me do a work placement with her, and to all of the UoB students and attendees who were so kind to me over the two days – it was a memorable and really enjoyable experience.

-

‘Intolerable and Insufferable Interference’: Financial Records as/and Family History

(or, why it was all my mother-in-law’s fault, by Henry Greswolde Lewis)

Account books and financial records rank alongside legal papers and letters as the items that were most frequently preserved in early modern family archives. Initially, at least, I found this somewhat surprising. As records of money spent and received, accounts books are neither as obviously useful nor as emotional evocative as the deeds and letters that they nestled alongside. And yet, when I started to take a closer look, I began to realise that many accounts were fraught with an emotional and sentimental significance that belied their apparently practical initial function. I’m currently writing a chapter on emotions, inheritance, and early modern account books for a collection by the brilliant Inheriting the Family team. In this post, I thought I’d introduce one of my favourite account books from that piece: the Greswolde family ‘Countbook’ in Warwickshire Record Office, which contains the records of at least five generations of Greswoldes across three centuries.

The ‘Countbook’ was begun by Henry Greswolde, a gentleman from Greete in Worcestershire, who in 1593 started a book to keep track of the prices his crops fetched at local markets. When his first son was born he made a note of his arrival among the records of sales, and as more children arrived Greswolde recorded the growth of the family unit alongside his financial accumulation. This combination of genealogical and economic record keeping wasn’t unusual. Lots of early modern account books became sites of family history, and many were passed through the generations as family heirlooms. While this dual use might partially be considered a prudent re-use of paper, there was also a religious dimension to early modern accounting that ensured it lent itself, conceptually and theologically, to family record keeping. Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the keeping of accounts was closely associated with the introspection and salvational self-examination that characterised so much post-Reformation Protestantism. It was a way, not just of tracing your financial position, but your spiritual state and the signs of God’s favour (or punishment). In this context, recording the gains and losses of one’s family – marriages, births, deaths – alongside financial gains and losses had a conceptual coherence: both were a way of tracing God’s providence and the signs of your own salvation.

However, the Greswolde text also testifies to some of the hazards of using account books as a site of family history, as well as the flexibility of their emotional meanings. In early modern accounting practice it was not uncommon for scribes to rip out pages that contained irrelevant material – debts repaid, accounts settled – and in the case of the Greswolde book several pages of vital family records were torn out sometime in the mid-seventeenth century. That the book’s third owner, the second Henry Greswolde, made a concerted effort to replicate and replace these records, even down to his grandfather’s habit of inserting his initials over entries ‘to signify his writing thereof’, testifies to the import attached to the material as well as the factual content of these records. Though Greswolde could not recreate the physical touch that had connected his ancestor to the book, he could recreate its visual appearance. Indeed, one of the most striking features of the Greswolde book is the consistent style used for entries, linking members of each generation in a shared material practice.

[Pages from the Greswolde Countbook (CR1291/437). Reproduced by kind permission of Warwickshire Country Record Office].

The financial accounts written in the Greswolde book, while not entirely jettisoned, became increasingly recessive as time went by, and were eventually themselves incorporated into the book’s genealogical function. In the mid-eighteenth century, David Lewis, husband of Mary Greswolde, went through the early accounts adding annotations that glossed them with additional, biographical information. By the late-eighteenth century, then, the Greswolde Countbook’s transition from financial to genealogical record was complete. However, as it passed through the generations there is evidence which suggests that the emotional meaning of the book, once prized as evidence of the longevity and continuity of the Greswolde line, became rather more ambivalent. Its final annotator, Henry Greswolde Lewis, did not have any children of his own, and he increasingly used the book, not to record family births and marriages, but to chronicle the ‘disastrous’ state of his own relationship, which he attributed to the ‘intolerable and insufferable […] interference’ of his mother-in-law. In Lewis’ hands, the book became less a site of family history than of self-justification: many of his entries were an attempt to absolve himself of responsibility for the breakdown of his marriage, while simultaneously lamenting the fact that this outcome had ‘prevented the Greswold family being perpetuated by me’. Even within a family, intergenerational books might possess different emotional registers for those who engaged with them. For Lewis, who had ultimately ‘failed’ to continue the family line, the emotions that the Countbook evoked were closer to regret and disappointment than the sense of pride and familial duty that had previously sustained it.

If you’d like to read more about inherited account books – and other fascinating chapters on inherited artefacts from across time and space! – keep an eye out for Inheriting the Family: Objects, Identities, and Emotions, ed. by Ashley Barnwell, Joanne Begiato, Tanya Evans, and Laura King (forthcoming with Bloomsbury).

-

Friction in the Archive

Last week I took a little jaunt to Lincolnshire to look at the collections of the Gregorys, a wealthy gentry family and one-time residents of Harlaxton Manor. I was on the trail of ‘last letters’ – that is, is incidences of people keeping the ‘last letter’ they received from a friend or family member before their death. These missives were often annotated with notes that trumpeted their ‘last letter’ status, and, in so doing, recipients sought to preserve an item’s sentimental significance – for themselves, and for future generations who may not perceive the emotional power of these often rather ordinary letters.

There are several ‘last letters’ in the Gregory collection. For example, a letter from Anne Gregory to her son, George De Ligne Gregory, in December 1785, was headed ‘The last letter’. On the back memorandum which read: ‘This was the last letter I ever received from my dear Mother, who was suddenly taken ill on 9thDecember following, & died on the 20th of that month’.

Letter from Anne Gregory to her son George de Ligne Gregory, 1785. Headed ‘The last letter’. Lincolnshire Archives] But just intriguing was a series of letters preserved by an earlier member of the family, Susanna Gregory (nee Williams), which had a rather different emotional register. Far from letters kept as affectionate mementos to lost loved ones, these letters were bitter, angry, filled with recrimination and ill will. The series begins with a copy of a letter Susanna received from her son, also (and confusingly) called George, in 1731. In it, he made several accusations against her, lambasting her tyrannical behaviour, negligence, and claiming she was so ‘blinded’ by her desire to die rich that she had overlooked the interests of her family. Susanna was clearly outraged, and, on her copy of the letter, she included a damning postscript:

‘this letter was sent to me inclosed in one to my Husband, the 10th of Febuary 1730, which letter was dated and sined by my son George Gregory, & that letter was full of falce accusations […] like this, but I having been his fathers wife above thirty years, & in that time he had longe Experience of my frugall carefull Conduct & knew his sons accusations to be falce, & mischevious, & malicious, & ungrattful to his tender affectionate Industrious Mother, so that it only Exposed him selfe, & provoked his Parents to resent his undutiful Base Behavior to them, Susanna Gregory’.

Here, Susanna transformed her son’s letter into a site of self-justification, defending her actions and character from the accusations of a ‘malicious’ son. The next letter in the series is her copy of her reply. This served a similar purpose, justifying her actions and impugning her son for his behaviour. The family archive became a site for negotiating conflict, and papers were preserved with an eye to presenting a particular version of events – in this case, Susanna’s.

Given that this dispute was between Susanna and her eldest son, who was the eventual heir of the Gregory fortune, I pondered why these letters had survived, without any effort at revision or rebuttal, in the family archive. Did Gregory simply never bother to read them? The answer presented itself when I pursued the pathway the papers took through the family. Though George Gregory, the vengeful son, was the eldest son and Gregory heir, Susanna survived her husband. On her death, she had her own wealth and personal effects to dispose of, including a family Bible that had descended down the Williams line and the Williams family silver. These she left – along with all her other effects, presumably including her papers – not to her eldest son, but to her daughter. This daughter died unmarried, leaving the Williams heirlooms to her nephew. Thus, they skipped over the angry son in question and were preserved by a line of the family who owed their wealth to the Williams legacy. Susanna’s careful bequeathal of her goods, and the loyalty of later family members, ensured that it was her version of events that was preserved in the family papers. Indeed, very few of her son’s papers survive in the collection, and those that do are largely uncontroversial: they certainly make no reference to this bitter family feud.

The complex case of Susanna Gregory’s letters shows that when considering which items (and emotions) appear in the archives, we need to pay careful attention to the pathways that papers took through families and the stories that their custodians were keen to tell. Family collections often appear to be sites of shared identity and consensus – but they were also places of conflict and friction, where family stories were contested and (re)constructed. And though we might assume that patrilineal descent would ensure the narratives of male heirs generally achieved precedence, in the case above it is the female voice that emerges victorious.

-

CFP: Family Archives and their Afterlives, 1400-present

CFP: Family Archives and their Afterlives, 1400–present

27-28 June 2023

University of Birmingham

From the muniments rooms of country estates to scrapbooks, photo albums, and boxes of papers and ephemera stored under the bed: our homes are sites of intergenerational collection and curation. We act as archivists, deciding which materials to keep, both for ourselves and for future generations who will, in time, face the same question. In the early modern period, anxieties over the loss of precious family paperwork were widespread. The sixteenth-century yeoman Robert Furse implored his son to ‘keep sure your wrytynges’, and the resolution of many an eighteenth-century novel – including Charlotte Smith’s The Old Manor House (1793) and a whole host of gothic fiction – turned on the adequate preservation (or otherwise) of family papers and the secrets contained therein.

Documents were kept in special vessels (initialled chests, boxes tied up with a loved one’s hair), they were bequeathed in wills, and, as public repositories became more widespread, some collectors attempted to imitate the practices of institutional archives in their own homes – or fought to get their materials included in (or excluded from) these collections. Today, we have the capacity to store an almost infinite quantity of material online – but many of us continue to prize the physical artefact, and books and readymade albums that purport to help us create and store our family archives are widely available.

Though in recent years the ‘archival turn’ has led to a renewed interest in the collections compiled by states and institutions, we know rather less about the materials accumulated by families and households. In the absence of the apparent hallmarks of modern archival practice – catalogues, indexes, and, perhaps most pertinently, professional authentication of their historical value – family papers are rarely approached as ‘archives’ – but, when they are transferred into local and national record offices, these same collections go on to form a significant part of our archival heritage. This conference seeks to bring together academics, archivists, and family historians to explore the family archive, in all its forms, from the medieval to the modern period.

Topics may include, but are by no means limited to:

- Approaches to the family archive: definitions, challenges, opportunities

- The contents and curation of specific family collections

- Access, circulation, and the ‘social life’ of archives

- Muniments and legal papers

- Exclusion and absence in the archive

- Archives and emotions

- The matriarchive and women as archivists

- Arrangement and organisation: cataloguing, inventories, storage, furniture

- Objects in/and the archive

- Visual and literary representations of family collections

- The relationship between family and institutional archives, including bequests, loans, and donations to local and national collections

- Destruction and dispersal

Please send a title, short bio, and abstract (c. 200-300 words) to: familyarchivesconference@gmail.com.

The deadline for submissions is 30 December 2022. We would be grateful if you could also let us know if you have any access requirements (e.g. online/hybrid attendance).

All papers will be considered for inclusion in an edited collection, estimated date of submission for chapters December 2023. Please make it clear on your submission if you do not wish your paper to be considered.

-

Little boxes, little boxes…

In our second workshop on “Objects as Archives” Professor Jill Journeaux shared some of her thoughts – and beautiful artworks – on family inheritances. From place settings to lacework, her talk was wide-ranging and thought-provoking: are family dinner tables a form of archiving? Some audience members also shared stories about their own treasured family heirlooms. Perhaps the most unconventional was a scrap of old dishcloth! An audio recording of this workshop is now available on the ‘Resources’ page of this site, and you can see more of Jill’s work on her website, drawingconversations.org.

Another conversation that arose during this talk was less about objects as archives than archives in objects: the ways paperwork might be stored in the home. One participant commented that, as an archivist, it is often not possible to preserve the materials a paper archive arrives in. Pressures of space and storage, for one, can be prohibitive, and she also commented that archivists do not always perceive the value in containers that a museum might.

This led me to thinking about the vessels in which early modern family archives were stored. From comments in wills and letters, it’s clear that boxes were a popular choice. In his will, the eighteenth-century clothier George Wansey bequeathed ‘all my Papers and Writings, which are in a Box in [my] Woolloft closet’ to his wife and eldest son, while in 1817 Elizabeth Dryden noted that ‘All the family writings which I have are in a long box bound with hair by my grandfathers initials’. The Johnson family papers, meanwhile, which I referred to in my first post, were kept in a ‘tin box’.

It is true though, that, in my research thus far, I have encountered relatively few original boxes or containers actually preserved in the archives. The Wansey collection, for example, is remarkably complete: but there is no sign of the box itself, once stowed safely away in the wool loft. However, there have been exceptions. The Greswolde family archive, for example, still resides in its original boxes, complete with the labelling and indexing instigated by its seventeenth century custodian, the rector Henry Greswolde.

[Box containing Greswolde family papers, mid 17thc, reproduced by kind permission of Warwickshire Record Office]

In other cases, it appears individual items had their own storage containers. Take, for example, “register” of the Bennett family, from Wiltshire, which recorded genealogical information, and was kept in a custom-made wooden box. Or the parchment roll recording the masters and scholars at Winchester College, c. 1769, and which formed part of the Frewen family archive: this still resides in its original – and once colourful — tube. From the fit it seems likely this container was purchased with, or specifically for, the document: it is certainly a more commercial product than the rather homespun Greswolde boxes.

As part of this project, I hope to uncover more examples archival containers that have successfully made their way into record offices. For these items are of more than incidental interest: they can help us to understand how archives were arranged, accessed, and used; their place within the material culture of the home; and hierarchies of value — does a special container, for example, denote an especially prized object? They might also help us to think about processes of transmission and archival selection – why have some boxes survived, while others have perished? And what might it mean to read archives detached from the objects that once mediated their organisation, access, and arrangement? Further examples of early modern archival containers are always welcome, so if you have come across any on your own travels do drop me an email!

-

Breast is…a bet?

This week I’m away on a research trip to the East Sussex Record Office in Brighton (it scores 10/10 for scenic jogging routes and nice dinner options!). I’m mainly looking at the Frewen family collection, and particularly a series of intergenerational account books which were used by successive family members.

Along the way, I came across what looks to be a wager between one John Frewen and his father, with the money riding, not on horses or cards, but on his wife’s breastfeeding habits. It reads:

‘August 28 1657

Memd: My Father is to pay me 5l if my wife doe <solely> nurse the child wherew[i]th she now goeth if not then I am to pay him soe much…’.

Does this represent John’s support for maternal breastfeeding, as opposed to the use of animal milk or wet nursing? Or his father’s scepticism at his daughter-in-law’s proposed feeding practice? It’s the kind of idiosyncratic, intriguing snippet that resides in so many family archives, and attests to the fact that account books could be so much more than just records of money spent and owed. I’m currently working on a chapter on intergenerational account books, so watch this space for more unexpected accounting activities!

-

‘Of no use’? Useless Papers and Useful Ideas

Welcome to the Family Archives in Early Modern England blog! In this space, I’ll be sharing some of my favourite finds and most perplexing papers as I voyage to family collections across the country.

For my inaugural post, I thought I’d share the small scrap of paper which first got me thinking about some of these materials as archives – that is, as intergenerational collections rather than as individual act of writing. It resides in the Jane Johnson papers in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Jane is perhaps best known for the impressive collection of handmade reading aids that she used to teach her children to write and for penning the first fairy story written in English. Her papers are brimming with poetry, illustrations, letters, reading notes and much else besides.

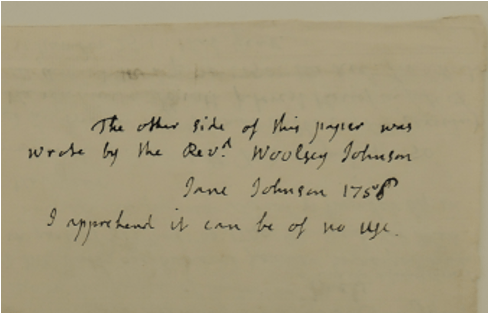

But what struck me, when I first leafed through the collection, wasn’t Jane’s own writings – fabulous as they are – but the notes she had penned on papers written in other hands. And especially on materials written by her husband, Woolsey Johnson, and his family. On this sheet here – my inspirational scrap — she’s written:

‘The other side of this paper was wrote by the Revd Woolsey Johnson. Jan Johnson 1756. I apprehend it can be of no use’.

Woolsey died in 1756 and on his death his papers passed to Jane. Through her annotations, Jane reveals the thought processes of a woman sorting through her deceased husband’s papers, deciding which items were worth keeping and which could safely be destroyed. The word ‘use’ is one that recurs again and again in Jane’s annotations: often in the context of an item being decreed ‘of no use’. And yet, in spite of this, Jane went to the trouble of inscribing and keeping these apparently useless items, passing them on to her daughter Barbara, who passed them to her nephew, whose wife passed them to her son in the early nineteenth century.

Jane’s note got me thinking: what might ‘use’ mean, in this context? In an age of increasing literacy, and increasing quantities of written material, how did early modern people decide what was, and wasn’t ‘useful’? What kinds of written remains were worth preserving, and which weren’t? And why? And thus, the germ of an idea, which eventually led to this, project was born.

(If you’d like to hear more about the Jane Johnson papers I will be giving papers on the Johnson family archive at several conferences this summer, including the Social History Society conference in July. There’s also an article in review so watch this space!)

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.