Welcome to the Family Archives in Early Modern England blog! In this space, I’ll be sharing some of my favourite finds and most perplexing papers as I voyage to family collections across the country.

For my inaugural post, I thought I’d share the small scrap of paper which first got me thinking about some of these materials as archives – that is, as intergenerational collections rather than as individual act of writing. It resides in the Jane Johnson papers in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Jane is perhaps best known for the impressive collection of handmade reading aids that she used to teach her children to write and for penning the first fairy story written in English. Her papers are brimming with poetry, illustrations, letters, reading notes and much else besides.

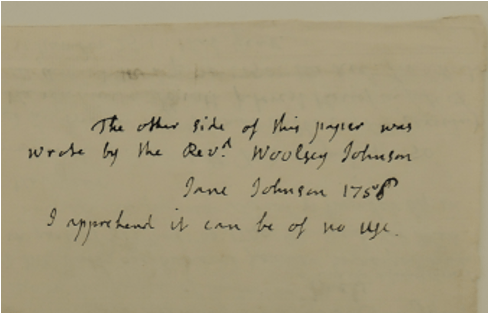

But what struck me, when I first leafed through the collection, wasn’t Jane’s own writings – fabulous as they are – but the notes she had penned on papers written in other hands. And especially on materials written by her husband, Woolsey Johnson, and his family. On this sheet here – my inspirational scrap — she’s written:

‘The other side of this paper was wrote by the Revd Woolsey Johnson. Jan Johnson 1756. I apprehend it can be of no use’.

Woolsey died in 1756 and on his death his papers passed to Jane. Through her annotations, Jane reveals the thought processes of a woman sorting through her deceased husband’s papers, deciding which items were worth keeping and which could safely be destroyed. The word ‘use’ is one that recurs again and again in Jane’s annotations: often in the context of an item being decreed ‘of no use’. And yet, in spite of this, Jane went to the trouble of inscribing and keeping these apparently useless items, passing them on to her daughter Barbara, who passed them to her nephew, whose wife passed them to her son in the early nineteenth century.

Jane’s note got me thinking: what might ‘use’ mean, in this context? In an age of increasing literacy, and increasing quantities of written material, how did early modern people decide what was, and wasn’t ‘useful’? What kinds of written remains were worth preserving, and which weren’t? And why? And thus, the germ of an idea, which eventually led to this, project was born.

(If you’d like to hear more about the Jane Johnson papers I will be giving papers on the Johnson family archive at several conferences this summer, including the Social History Society conference in July. There’s also an article in review so watch this space!)

Leave a comment